I like paddling all through the winter. Some of my most beautiful paddles have been in a December or a February. Two things you get used to from habitual winter paddling are: 1) you ALWAYS wear your drysuit, and 2) you are ALWAYS willing to cancel your plans based on last minute weather predictions.

It was mid-April this early spring, a time when many are itching to get back outdoors. But also a time when conditions can still be very unpredictable. My original plans were to go paddling in Port Madison on Saturday with some friends, but I cancelled due to the stormy forecast.

Then, on Sunday, I read the horrid news with gut-wrenching frustration – it was SO easily avoided, yet two kayakers died unnecessarily and a third landed in critical condition at Harborview.

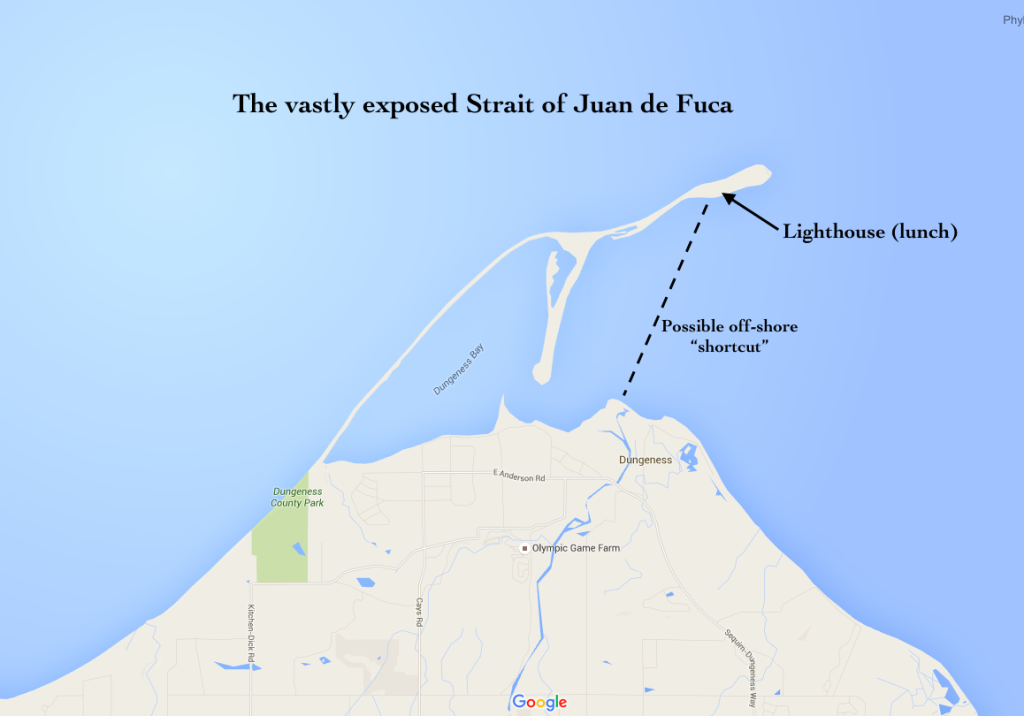

The facts, in brief: A small group of “experienced” kayakers – a church group who frequently do outings together (both paddling and hiking) – launched into what seemed a beautiful day out of Sequim, paddling out to the lighthouse at the end of Dungeness Spit, and enjoying lunch on the beach. Then, on their return, they were caught off shore in “unexpected” high winds and steep waves. Three kayaks were capsized, with two dying and one rescued and evacuated to Harbourview in critical condition.

It is ironic that many media reported them as “experienced kayakers”. Personally, whenever I hear that “experienced” hikers/boaters/climbers/skiers/whatever die, I find myself asking desperately – “If those experienced people die from these activities, then surely it must be extremely dangerous, and therefore I should stay home and hide under my bed instead of striking off into the hazards of wilderness adventure!”

Let’s take a closer look at the actions of these “experienced kayakers”:

- They went out in early April, when the waters of the Salish Sea average in the forties, conditions in which hypothermic conditions begin after 5 minutes of immersion, and death can occur within an hour.

- They went out in the Salish Sea at this time without sufficient thermal protection. (I read one report that “some of them” were wearing wetsuits (the ones that didn’t capsize, and survived), which do not provide sufficient thermal protection in winter (April) conditions. At that time of year, dry suits are a must. They didn’t even all have spray skirts (which prevent swamping of a boat when waves wash over). Let’s be clear: Clothing that may keep you warm in cold air is useless when you are immersed in cold water. Only keeping that clothing dry (as in a dry suit) will provide adequate thermal protection in winter cold water conditions.

- They went out without proper assessment of the weather. It didn’t take much for me to listen to the marine forecast and choose to cancel my paddle in the relatively protected waters in Puget Sound. Hello – high wind warnings several days in advance. This group went out into the much more exposed waters of the Straight of Juan de Fuca, where the wind forecast was in excess of 30 knots. I would not choose to go out in my offshore-capable 30-foot sailboat with that prediction.

- And given all of that, they also chose to paddle well away from the shoreline. I can’t imagine why – except to think they may have wanted to shorten their paddle by cutting straight from the end of the spit to Sequim. It is a VERY risky thing to do – in winter – in cold water – without thermal protection – without spray skirts – without having thoroughly assessed the weather forecast.

The opportunities to enjoy the spectacular beauty and closeness to nature that only kayaking can provide are endless. And one does not have to risk ones life for these endless opportunities. There are basic precautions and skills that can be learned and observed to keep us safe and partaking of this amazing sport for the rest of our long-lived lives.